How Algorithms Are Quietly Redefining Contemporary Design

At this year’s ICFF, the Talk “Exploring Creative Potential with New Technologies” dug into a question that’s becoming impossible for designers to ignore:

How are new technologies, not just in production, but in commercialization and every step in between, reshaping contemporary design?

Moderated by Jaime Derringer (Founder of Design Milk and Head of Brand at TRAME), the conversation brought together three practitioners who’ve been working with algorithms long before “AI” was a headline:

- Benjamin Aranda — Architect, co-founder of Aranda\Lasch, professor at The Cooper Union

- David Schwarz — Co-founder of experience design studio HUSH

- Emily Edelman — Artist, designer, and algorithmic artist

Rather than focusing on Midjourney prompts or image generators, the session reframed technology in a broader, more human, and frankly more useful way.

(Image above: Exploring Infinite Creative Potential with New Technologies panel, from left to right: Jaime Derringer, Emily Edelman, David Schwarz, Benjamin Aranda | photo: Jenna Bascom Photography)

Algorithms: Older Than AI, Already in Your Practice

The first move was to demystify the word “algorithm.”

Strip away the jargon and an algorithm is just a set of instructions. If you’ve ever given a fabricator step-by-step directions, built a system for how a pattern repeats, or codified how a detail is resolved on every project, you’ve already designed one.

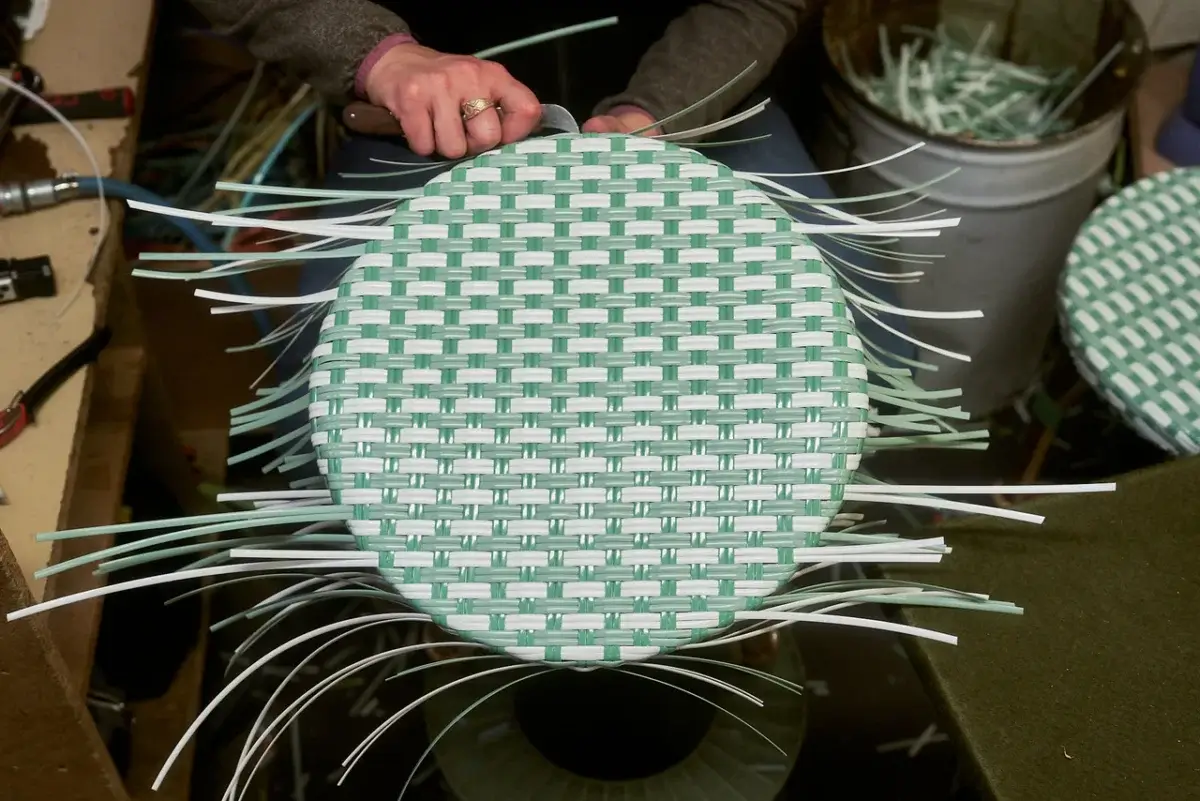

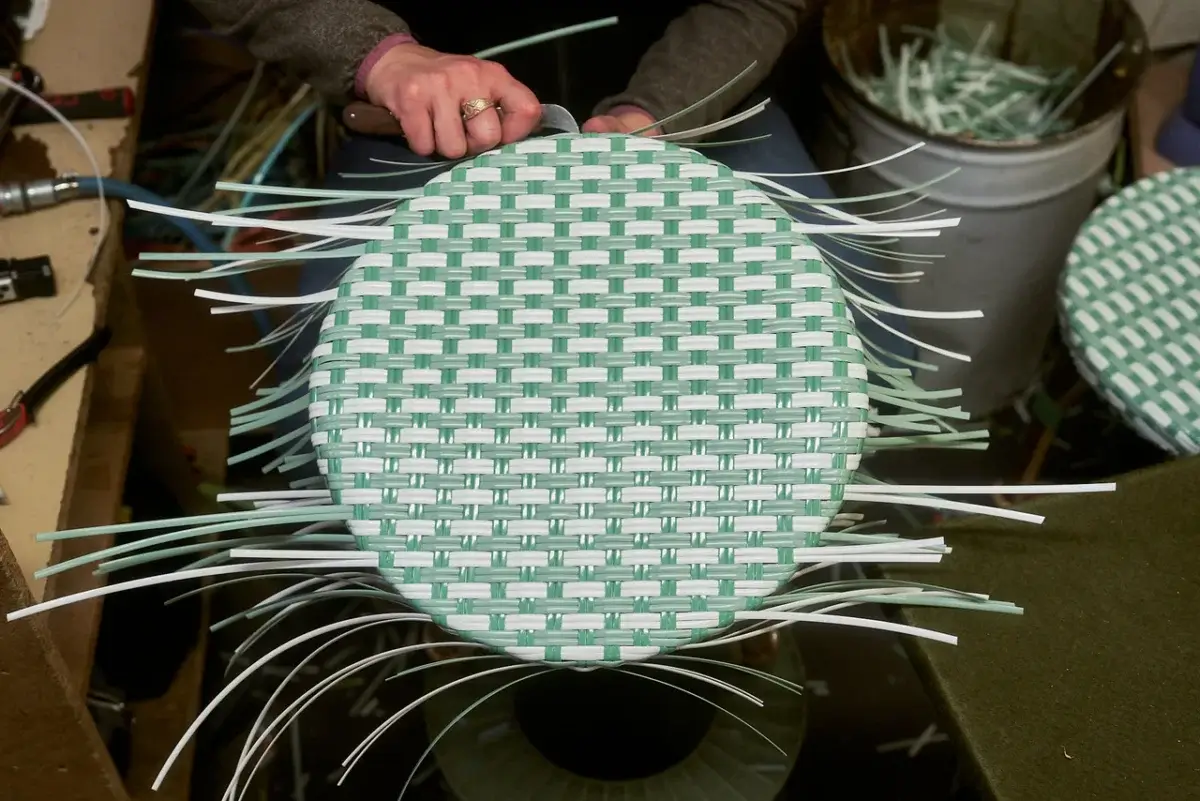

Aranda drew the line all the way back to weaving and basketry: ups and downs in a weave, the logic of a coil, rules for how materials come together. These are physical, cultural algorithms—systems humans have used for thousands of years to embed knowledge into objects.

New technologies don’t introduce algorithms to design; they amplify them.

From Making One Thing to Designing the System

For Edelman, working with code means designing rules and randomness rather than a single final image.

She compared two phases of her own career:

- Pre-code: giant Illustrator artboards filled with poster variations, different type scales, backgrounds, and compositions, all built manually.

- With code: the same instinct to iterate, but now an algorithm can generate tens of thousands of variations in seconds.

The mindset, she emphasized, is the real shift: thinking in terms of variables, inputs, and constraints instead of just single outcomes. Coding is one path into that, but it’s not the only one. A designer can think algorithmically with a spreadsheet, a deck of cards, or a dice roll.

What changes with technology is the scale and speed at which you can explore.

When Quantity Is Infinite, Curation Becomes the Craft

If algorithms can generate 10,000 options, the question becomes: when do you stop?

Schwarz described generative tools as a way to open the field as wide as possible, especially early in a project. His studio has used sustainability data, for example, to drive form:

- Using embodied carbon data of materials to deform objects and sculptural forms

- Turning a full year of the studio’s own business metrics into a physical “annual report” sculpture—52 shapes, each representing a week

What used to be impossible becomes routine: creating 100 unique sculptures for a biennial, or whole families of objects, all coherently related yet formally distinct.

But this isn’t about hitting “randomize” and walking away. It’s about what happens next.

As Jaime pointed out, in a world saturated with generated content, taste, editing, and point of view become the real differentiators. Designers shift from “making one precious object” to defining:

- The system that generates a universe of options

- The filters that decide which of those options deserve to exist

In that context, the designer’s role looks less like a maker and more like a curator, editor, and storyteller.

Technology as Infrastructure for Craft

One of the most compelling threads of the conversation was about using technology to support craft rather than replace it.

Aranda talked about:

In the Maison Drucker project, his team worked to encode the craftsperson’s knowledge into software: how colors combine, how patterns are woven, how structural logic and aesthetics intertwine. The result isn’t a robot that spits out chairs; it’s a system that lets human makers explore new variations and configurations in line with their heritage and expertise.

Derringer underscored TRAME’s aim, which is to use technology to preserve and extend cultural heritage, not to outsource it. The algorithm becomes a way to document and evolve a tradition, keeping artisans central.

In a moment when “automation” often means job loss, this is a different model: technology as creative infrastructure for human labor, not a substitute for it.

Bias, Ethics, and the Question of Credit

The panel was equally clear-eyed about the risks of today’s algorithmic systems.

Aranda called out the inequities baked into AI: models trained on an internet that is itself uneven and biased, with virtually no obligation to credit or compensate the people whose work fuels those systems.

When an audience member asked how to ethically describe tools, datasets, or other artists as “collaborators,” Edelman turned to a familiar analogue, the colophon in books, which is a space for transparently listing typefaces, paper, printers, photographers.

She doesn’t see the computer as a co-author. For her, the creative authorship lies in:

- Choosing inputs and constraints

- Deciding where randomness is allowed

- Curating which outputs go into the world

But she argued that being open and specific about tools and sources is part of ethical practice in an algorithmic age.

The subtext here is that we need better legal and cultural frameworks around attribution in AI, but we don’t have to wait for them to start behaving more transparently as designers.

So Where Do Humans Still Matter?

Audience questions inevitably turned to the future: automated CAD, AI-driven “instant interiors,” clients who think prompt-based tools are “good enough.”

The panel’s answer wasn’t nostalgic, but it was firmly human:

- On site, in reality: Architects and designers remain critical in the translation from drawing to built form; catching discrepancies, responding to materials, and defending the integrity of the design.

- With clients and users: Much of design work happens in conversation—negotiating priorities, unpacking needs, challenging assumptions. That kind of messy, emotional, contextual dialogue doesn’t compress neatly into a prompt box.

- On the level of lived experience: As Edelman put it, AI doesn’t live with us. It doesn’t inhabit a room, sit in a chair, or move through a city. Designers do, and they design for other people who do.

The consensus wasn’t “don’t use these tools.” It was closer to “use these tools critically, intentionally, and humanely.”

The Bottom Line

New technologies aren’t simply changing how we produce and sell design; they’re changing what it means to design at all.

They invite us to:

- Think in systems and rules, not just one-off objects

- Treat data as a design material

- Shift our value from singular authorship toward curation, judgment, and narrative

- Use code and computation to amplify craft, culture, and heritage—not erase them

- Stay vigilant about bias, attribution, and the power structures embedded in our tools

If we’re thoughtful about it, the future of design with algorithms doesn’t look like humans versus machines.

It looks like humans designing better systems—and then using them to make more meaningful things.

More from ICFF:

Opiary: Bringing People and Nature Together

Global Sourcing in Design